You may have heard your grandparents talking about parenting with a "united front." That unity between parents has been superseded in today's society by a priority for open, honest communication with children, sometimes even if it is about their other parent, and that causes problems for children.

In your grandparents' day, the family with two parents was typical. Children in today's society may have multiple parents and caregivers. Sometimes they have one, three, or four parents. Sometimes grandparents or aunts and uncles help with parenting. According to a Census Bureau report, only half of this country's children live in traditional two-parent families.

It’s important those adults who guide children's lives guide them in a united and reasonably consistent way. Even though the adults may have some differences in their preferred styles of parenting, the view from the children's perspective should be of fairly similar expectations, efforts, and limits.

It’s important those adults who guide children's lives guide them in a united and reasonably consistent way. Even though the adults may have some differences in their preferred styles of parenting, the view from the children's perspective should be of fairly similar expectations, efforts, and limits.

If adults are consistent with each other, children will know what's expected of them. They’ll also understand that they cannot avoid doing what feels a little hard or scary or challenging by the protection of another adult. Benjamin Spock, in his book A Better World for Our Children, stated it well: “. . . the best-behaved children are those whose parents are clear about what they want from their children and go about it in a friendly way.”

PARENT RIVALRY

Competition invades our families. Underlying parent rivalry are parents' concerns about being good parents. That wish to be a good parent may be internalized as being the "better" parent. Sometimes a parent's effort to be better may cause the other parent to feel that he or she can never be good enough.

One parent may see him or herself as being the best parent by being kind, caring, loving, and understanding. The other parent may see him or herself as being best based on being respected and expecting a child to take on responsibilities and showing self-discipline. Although each parent sees him or herself in these ways, he or she doesn't necessarily see the partner in the way that the partner describes him or herself. The parent who sees him or herself as kind and caring, therefore, may be viewed by the other parent as being overprotective. The parent who sees him or herself as being disciplined and responsible may be viewed by the other parent as being rigid and too strict. They don't see each other in the same way as they see themselves, so they just decide that because their own ways are better, they must change the other parent.

After fruitless efforts to change each other, they give up and decide that they must balance out the other parent by becoming more extreme in what they believe. The kind, caring parent becomes more protective in order to shelter the children from the parent who expects too much. The expecting parent becomes more demanding to balance out the overprotective parent. The more one expects, the more the other protects. The more the second protects, the more the first expects. The “balancing act” approach draws them further and further apart, leaving the children caught in the middle, not sure they can ever meet one parent’s expectations, but absolutely certain the second parent will approve of almost everything.

If children face parents who have contradictory expectations, and lack the confidence to meet the expectations of one of their parents, they turn to the other parent who not only unconditionally supports them, but accidentally teaches them "the easy way out." The kind and caring parents, without recognizing the problem they're causing their children, unintentionally protect their children when they face challenge. When children have grown up in an environment where one adult has provided an easy way out for them, they develop the habit of avoiding challenge.

If children face parents who have contradictory expectations, and lack the confidence to meet the expectations of one of their parents, they turn to the other parent who not only unconditionally supports them, but accidentally teaches them "the easy way out." The kind and caring parents, without recognizing the problem they're causing their children, unintentionally protect their children when they face challenge. When children have grown up in an environment where one adult has provided an easy way out for them, they develop the habit of avoiding challenge.

The balancing act increases in complexity when there are three or four parents involved. Each parent is desperately anxious to provide the best parenting to keep their children's love. After divorce, parents are more likely to believe they can tempt children to love them by protecting them the most, doing too much for them, or buying them more.

In my books, I’ve described the four competitive rituals that take place between parents as "ogre and dummy games." There are variations of ogre and dummy games that involve stepparents, grandparents, and aunts and uncles, and those that change between childhood and adolescence. I’ll only have room to describe two of these rituals, but they will be graphic enough for you to easily imagine how they could happen in your own home if you don't make specific efforts to maintain a united front. You can read about the other two in either of my books, How to Parent So Children Will Learn or Why Bright Kids Get Poor Grades.

FATHER IS AN OGRE

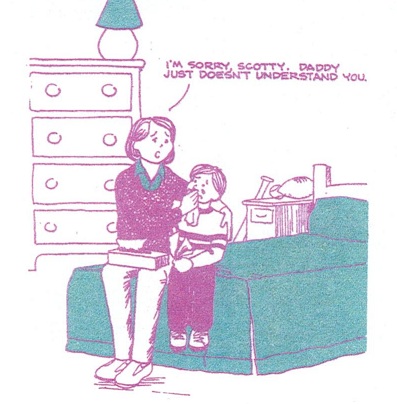

In the family where this ritual takes place, the father is viewed by outsiders as successful and powerful, the mother as kind and caring. A closer view of the family shows a father who has high expectations for his children. They’re perceived as being too high by the mother and the children. The children learn to bypass Father's authority by appealing to their kind, sweet mother to avoid his requests. Mother either

Dad may escape through his continuous work, which further convinces his children to avoid being like their "workaholic" father. As the children mature, their learned opposition to their father often generalizes to angry opposition to other authority figures as well.

MOTHER IS THE MOUSE OF THE HOUSE

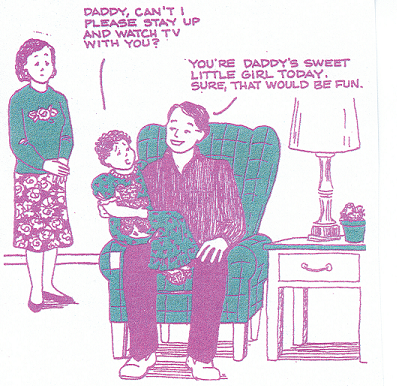

The ritual where mothers are made to seem like dummies, which results in rebellious adolescent daughters, begins with a conspiratorial relationship between the father and daughter (Karen). It is a special alliance that pairs Dad and his perfect little girl with each other but, by definition, gives Mom the role of "not too bright" or somehow "out of it."

During early childhood, Dad never says no to Karen. She has a special way of winding him around her little finger. Mom admires the relationship, but she is really not part of it. Everyone agrees that Karen is perfect.

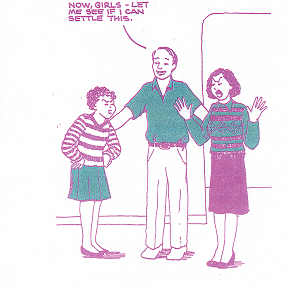

Preadolescence arrives and Mom notes a change. Battles are taking place between her daughter and herself. Karen often goes to Dad because she is having trouble with Mom. He mediates and smoothes things over.

taking place between her daughter and herself. Karen often goes to Dad because she is having trouble with Mom. He mediates and smoothes things over.

Karen enters middle school, shows signs of maturing physically, and Dad suddenly begins to worry about his perfect daughter. Danger lurks in the corridors, in the lavatories, at school dances, and at preteen parties. Dad begins his tirade of cautions about cigarettes, alcohol, drugs, and most of all, boys. He must protect his perfect child from the evils of growing up. He decides it's time for rules.

Rules mean "no’s" and Karen has really never received a no from Dad and those no’s feel terrible. She appeals to Mom. Mom sees her first opportunity to build a closeness to her daughter. Now there is a new alliance—Mom and Karen against Dad. When that works, Karen is happy. When it doesn't, Karen returns to Dad. Karen learns to manipulate back and forth.

Now Karen is in high school. Her parents are worried. They suddenly realize it's time for a united front. Mom and Dad are on the same team, and Karen stands alone against them. They're saying “no” more frequently, and even when she performs her best manipulations, Karen can’t change their minds. She reaches out to her peers and finds some peers who are having similar problems with their parents. They help her to understand that some parents just aren't "with it." Karen now has her own team. Together they will prove they can oppose their parents.

Now Mom and Dad are really anxious. Karen hangs out with the "losers," and her parents have found cigarettes in her room. How can they trust her? They set curfews, but Karen climbs out the window. Now Karen’s smoking pot. They think she's sleeping with a “druggee.” Her journal, which she leaves out on her desk, says she "hates” her parents. She's disrespectful, uses foul language, ignores their rules, and her formerly A and B grades drop to D's and F's. She skips classes. Her parents can't understand what happened to the sweet little girl they remember.

she's sleeping with a “druggee.” Her journal, which she leaves out on her desk, says she "hates” her parents. She's disrespectful, uses foul language, ignores their rules, and her formerly A and B grades drop to D's and F's. She skips classes. Her parents can't understand what happened to the sweet little girl they remember.

Rebellious Karen, who had too much power as a small child and whose father unwittingly encouraged her to compete with her mother, feels rejected, unloved, and out of control. Girls like this take various paths, but they all signal the same sense of lack of power, which they feel mainly because they were given too much power as children. Some say their parents (especially their fathers) don’t love them, and they must have love. When a girl is in a boy's arms she mistakenly believes that he loves her, and it feels good. When he leaves her bed for the next one, she feels rejected and embittered and easily accepts the next invitation that feels like love.

Other girls express rebellion silently. Bulimia, anorexia nervosa, depression, and suicide attempts are powerful ways of expressing feelings of loss of control. These illnesses leave parents feeling helpless and blaming each other. They put adolescents or young adults in control of their parents but not in control of themselves. The wink-of-the-eye between Daddy and his little girl that puts Mother down as the "Mouse of the House" will become the preadolescent daughter's roll-of-the eyes at her mother. When Father says no as well, that daughter feels rejected by both Mother and Father, increasing the likelihood that she’ll go from bed to bed in search of love to substitute for the rejection she now feels.

HOW TO AVOID OGRE AND DUMMY GAMES

The key to avoiding ogre and dummy games is respect. If parents both voice and show respect for each other, children will respect their parents. Ogre and dummy games can be corrected by parents recognizing or being aware that they exist; they require cooperation and compromise. Here are some suggestions:

Make it clear to your children that you value and respect the intelligence of your spouse. Don't put your spouse down except in jest and only when it's absolutely clear that you're joking. Use conversations with your children to point out the excellent qualities of your husband or wife.

Be sure to describe your spouse's career in respectful terms. In that way, neither of you feels as if you're doing work that the other doesn't value.

Don't join in an alliance with your children against your spouse in any way that suggests disrespect. Sometimes parents do this subtly, as in, "I agree with you, but I'm not sure I can convince your mom (or dad)." If you communicate to your children that you value their other parent, it will almost always be good for your children, for your spouse, and for you. In adolescence, just a few slips may initiate disrespect.

Reassure your oppositional children frequently of their parents' mutual support for them. Be positively firm in not permitting them to manipulate either of you. They may perceive spousal support of each other as a betrayal of themselves and will feel hurt or depressed. You should assure them frequently that spouses can respect each other and still love their children. One of the parents (the "good" one) will easily be placed in the position of mediator by these children in order to persuade the other, unless the parent absolutely refuses to play that role.

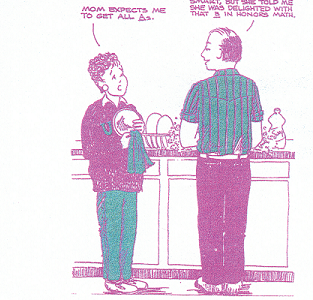

When your children come to you to complain about their father or mother expecting too much of them, be alert not to get caught in the manipulations. They're hoping you'll help them get out of what the other parent has asked them to do. You'll want to respond in kindness while maintaining a message of respect for your spouse. If the child says, "Mother (or Father) expects too much of me," an example of an appropriate answer is:

father or mother expecting too much of them, be alert not to get caught in the manipulations. They're hoping you'll help them get out of what the other parent has asked them to do. You'll want to respond in kindness while maintaining a message of respect for your spouse. If the child says, "Mother (or Father) expects too much of me," an example of an appropriate answer is:

"Your mother expects this of you because she knows you're capable. If she didn't expect it of you, it would mean that she didn't believe you could do it. You should be pleased that your mom expects it. After you do it, Mom will be proud, and you'll feel good."

This kind of response, whether related to Father or Mother, gives children a message of confidence. Most of all, it provides the united expectations that permit your children to build self-confidence through achievement.

Abraham Lincoln addressed our nation as he faced the hard decisions that led to the Civil War and concluded, "A house divided against itself cannot stand." Perhaps this important observation about our country has even more applicability within our families.

Adapted from:

How to Parent So Children Will Learn by Sylvia Rimm, (Scottsdale, AZ, Great Potential Press, ©2008)

Why Bright Kids Get Poor Grades by Sylvia Rimm, (Scottsdale, AZ, Great Potential Press, ©2008)

©2011 by Sylvia B. Rimm. All rights reserved. This publication, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without written permission of the author.