THE PRESSURE TO BE POPULAR

Parents may call it "well adjusted" and they may see social adjustment as more important than being "smart." Elementary teachers describe it as "good peer relationships" and frequently prioritize it ahead of intellectual challenge. If bright children internalize these adult messages, they typically do adjust well in elementary school and do not appear pressured. They learn to enjoy the comforts of social acceptance, and they play down their own intellectual differences.

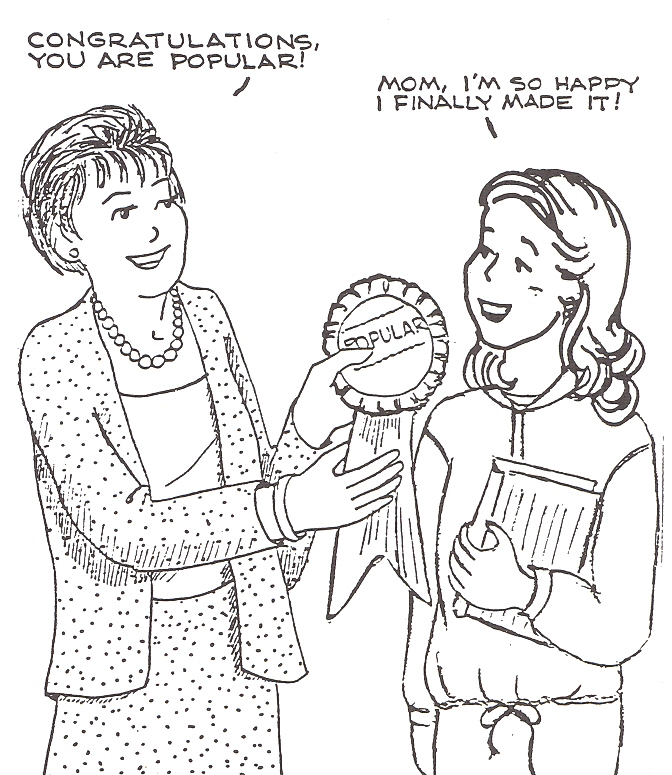

The goal of "good social adjustment" takes on a different pressure by preadolescence. By then, adjustment translates to popularity, and becoming peer-adjusted forces children into a value system that may differ significantly from what their parents and teachers earlier described as social adjustment. Popularity is the competitive stage of social adjustment. Kids try to be the "most" well adjusted, to be leaders in the "in" crowd, depending on how they define "in." The popular message may involve athletics, student government, drama, and music, or it may mean alcohol, drugs, violence, and/or sexual promiscuity. Whether they or others call them jocks, preppies, dirts, or skaters, their name confers particular styles of dress, types of music, kinds of activities, and social conformity with their crowd or gang. It doesn't mean getting

The goal of "good social adjustment" takes on a different pressure by preadolescence. By then, adjustment translates to popularity, and becoming peer-adjusted forces children into a value system that may differ significantly from what their parents and teachers earlier described as social adjustment. Popularity is the competitive stage of social adjustment. Kids try to be the "most" well adjusted, to be leaders in the "in" crowd, depending on how they define "in." The popular message may involve athletics, student government, drama, and music, or it may mean alcohol, drugs, violence, and/or sexual promiscuity. Whether they or others call them jocks, preppies, dirts, or skaters, their name confers particular styles of dress, types of music, kinds of activities, and social conformity with their crowd or gang. It doesn't mean getting

As or excitement about learning. The value system that fits in with popularity also includes very intense pressure. Popularity is typically a comparative perfectionistic goal, and one rarely feels popular or pretty enough. some case examples of the pressure to be popular follow:

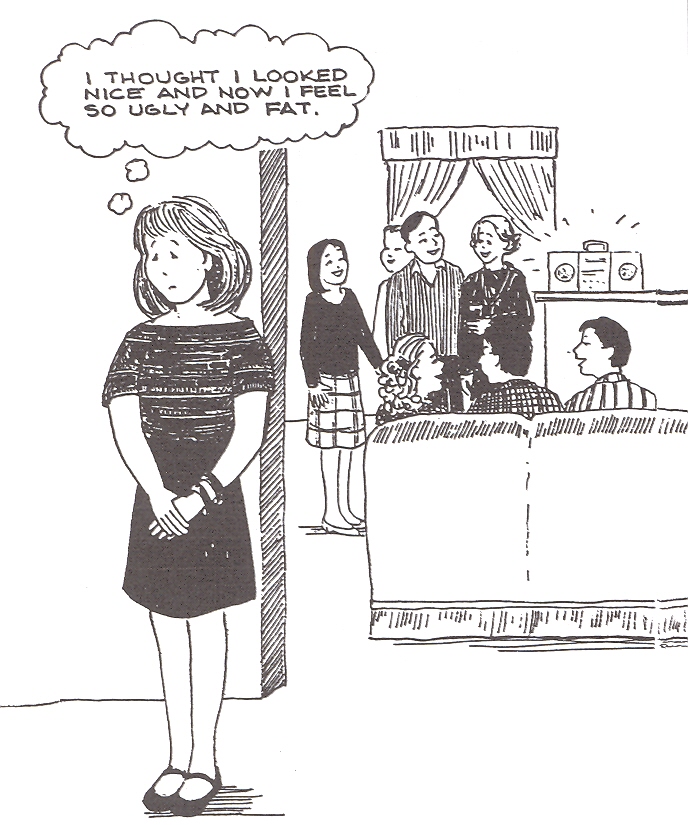

BETH

Beth's desperate concern with popularity centered mainly on clothes and appearances. Her efforts to be attractive and admired for being pretty were emphasized by her family involvements in "Miss Teen" pageants. Cs were acceptable academic goals while weight control and fashion were top priorities. Beth spent hours with make-up and mirrors, and was determined to be very attractive. Although her reflection usually pleased her before she left home, she often felt depressed at parties. She compared herself to every other female in attendance and always thought she fell short of her competitive standards for beauty. Normal friendships took on the pressure of beauty contests, and her obsession with weight and thinness propelled her toward eating disorders rather than involvement in healthy interests, learning, or productive creativity.

SCOTT

Scott had struggled with loneliness as long as he could remember. He always had some friends but his memories of torment by other kids overshadowed his memory of normal peer relationships. When he moved from his small elementary school to a large junior high school, he felt the greatest loneliness. In gym class, his modesty and inexperience caused him to hesitate about pulling his pants down in the boys' locker room. He shared his feelings of embarrassment with another boy. The word spread immediately and the entire locker room chanted at him. He was in tenth grade when he described the experience, but his intense pain remained alive and was part of his drive and determination to be socially accepted almost regardless of personal or intellectual cost. His reputation as a "geek" remained, but he pursued social acceptance relentlessly. Intellectual excellence became a low priority for him, and his school performance was, at best, erratic.

HOW PARENTS AND TEACHERS CAN HELP

Encourage your children's active interests and share your own interests with them.

Encourage your children's active interests and share your own interests with them.- Keep at least one day a week for family activities without peers.

- Encourage children to work or play alone (without television, siblings, or friends) for a part of each day.

- Don't become anxious for them if they're not invited to every party. Instead, be matter-of-fact and explain that they can't be everyone's friends.

- Suggest they be selective in their friendships. While they should certainly be pleasant to all kids, special friends should be selected based on good values, shared interests, and commitments to friendships.

- Explain about the importance of independent early so they have the courage to avoid conformity later.

- Be a role model for appropriate relationships. Don't let your children talk about others behind their backs and don't let them see you going into adult peer relationships for your own peer conformity.

- Remind them that there is life beyond middle and high school. While they surely should enjoy a reasonable social life, the main purpose of school is education. It will give them more adult choices.

- Friendship is not competition, but cooperation. They don't need the most friends, or the most statusConly a few true friends who share interests and values. Remind yourself not to be disappointed if they are not popular. That will convey itself to your children. Don't label one of your children the "social" child.

©2010 by Sylvia B. Rimm. All rights reserved. This publication, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without written permission of the author.