The Fashion of Passion - Are We Setting Goals Too High?

Sylvia B. Rimm, Ph.D.

Director, Family Achievement Clinic

Clinical Professor, Case School of Medicine

July 2015

A most frequent and fashionable mantra given today by educators, parents and well-meaning counselors to adolescents and young adults is "find your passions." It is heard and seen everywhere - at airports, in advertisements, at high school and college graduation addresses, from successful parents and teachers, and even on Starbucks coffee mugs.

Here are a few of the recent quotes and advertisements:

- A poster on a public school wall: “Do What You Love and Do It Often”

- A poster in an airport: "Mia Hamm - Kicked her way to the top. Passion. Pass It On."

- An internet advertisement: "Turn Your Passion into a Career."

- An employment ad: "Breaking news! Schools searching for 10 educators passionate about learning!"

- On Starbucks coffee mugs by the famed and highly successful Oprah Winfrey: "Follow your passion. It will lead you to your purpose."

- Perhaps most comically, on a giant dumpster: Trashin' is our Passion."

Passions, as defined in the Merriam Webster dictionary (2007), are "strong feelings," and "emotions as distinguished from reason." We must search beyond the obvious to understand what leads reasonable and responsible adults to guide adolescents who are already at the most imaginative and emotional stages in their development to believe that they are entitled to "follow their feelings to find what they will be doing for the rest of their lives?" The appropriate term for young people who believe they are entitled to do only what gives them emotional pleasure is "narcissism."

Highly intelligent adults who are responsible for guiding young people are allowing them and even persuading them to follow only their own feelings, rather than combining feelings with reason and logic or accepting advice from experienced adults for determining their future directions. Dr. Gordon Marino, Professor of Philosophy at St. Olaf College questions, "Is ‘do what you love’ wisdom or malarkey?" (2014). One must explore how this irresponsible "malarkey" has become so omnipresent?

The Research That Supports Passion

Soccer player Mia Hamm is undoubtedly passionate about playing her sport and is successful as well. Teachers who are passionate about their work are actually more likely to inspire students and Oprah Winfrey is both passionate and extraordinarily successful in her career, so why not encourage this message of searching for one's passion? In a 15-year follow-up study of a sample of successful women (Rimm, Rimm-Kauffmann & Rimm, 2014), most of the successful women emphasized that they were passionate about their work. Lest readers think I only quote women, I asked my husband and sons how they feel about their work. They admitted they loved their work, at least much of the time. Educational administrators who are passionate about their work at least some of the time are more likely to be effective. Furthermore, I am often very passionate about my own work. Enjoying your work, or intrinsic motivation, absolutely enhances learning and should surely be part of an adolescent search for meaning, so what can be wrong with this epidemic of advice to search for passions?

The Problems with Passion

The major problems with communicating to gifted children goals for becoming passionate about their work is that adults are either giving them a message of entitlement, or even worse, inspiring them to set their goals too high at a time in their development when they should be searching for their identity with both their emotions and their reasoning abilities.

Bright children often internalize perfectionistic, highly competitive pressures. Now adults have added a new pressure that causes them to believe that they must find a “perfect passion." Research on motivation (Davis, Rimm, & Siegle, 2011; Hostettler, 1989) finds that achieving children and adults set realistic expectations and those expectations build their self-efficacy. Underachievers set goals too high or too low, both of which defeat motivation, by serving as excuses for avoiding effort.

There is a huge difference in the way successful adults define and understand passion in regard to their work and the way in which imaginative and emotional children understand passion. The following statements are likely to be shared by adults who realistically enjoy their work:

- I absolutely love my work 'sometimes!'

- I made excellent progress on my project!

- My journal article was finally published!

- I’m making a difference and helping people!

- I made a sale today!

- I’m helping to design a bridge to alleviate traffic downtown!

- After many, many years of hard work and rejection, my art has finally been accepted into an art museum!

- My students’ science project won a prize!

Children, adolescents and young adults hear and interpret expectations of passions very differently. Here are some examples:

5th grade boy: "I'm hoping to be a professional basketball player, but I won't play on a team because it's too competitive."

Ninth-grade boy (with gaming addiction): "I could become a reviewer of video games. I know them all."

Semi-musically talented guitar player: "I’m following my passions and hope to become a rock star."

Or in contrast:

Seventh-grade boy: "Why doesn’t the teacher teach us something we love; I don’t like math, it's too boring."

Eighth-grade boy: "I plan to design video games. I absolutely hate to write. I won't do that homework. The teacher is not teaching me right."

Teenage girl: "My parents expect me to be perfect, the work is too hard."

College student: "My passion is to become a writer, but I’m not signing up for a writing course. It will destroy my personal style."

Parents and teachers also share these messages with me in my clinic and school about students who they want to help find their passions:

- Our son goes from sport to sport, activity to activity, but doesn’t persevere.

- My student doesn't seem interested in anything.

- My student just wants to get by and do the least he can.

- I can’t drag my son away from video games.

- My daughter won't take notes, but instead draws. Her passion is art and I think she should not have to take notes. I want her to follow her passions.

- My son has good musical talent but won’t take lessons. Instead, he thinks it's important to just play for himself.

The Sad Effect of Too High Expectations

Young people who have internalized too high expectations will feel extraordinary anxiety or are at high risk for depression, with some experiencing both. Anxious children may habitually avoid effort and competition. Examples of such avoidance include the boy who won’t even try to play on a basketball team although he loves the sport; the child identified as gifted who refuses to be in the gifted program because she doesn't think she is smart enough or the writer who won’t take a writing course because he fears criticism. Children who go from one activity to another and quit as soon as an activity becomes difficult are searching for their passions, but they equate passions with finding tasks easy and fun. When they fear failure, they discontinue the activity because they no longer believe the activity is their passion.

Examples of depressed children include those who give up on joining any activities or who refuse to do homework. One very talented young woman set her heart (and passion) on becoming a solo violinist until she found her talent was only sufficient to play in a symphony orchestra, but not as a soloist. She became so depressed that she could no longer even listen to music although music had been her passion during her entire childhood.

Passions Should Be Tempered With Reason

Some children feel passionate about unrealistic dreams for their futures, while others can’t seem to become engaged in activities at all. The first are at risk of depression; the second are likely to become underachievers (Rimm, 2008) because they are so fearful of making effort.

For those young people who are intensely involved in exclusive activities that they hope will lead them to a career, educators and parents can help them to investigate opportunities toward pursuing careers they may feel passionate about. Acrostic REAL (Figure 1) encourages students to be strategic, emphasizes a growth mindset (Dweck, 2006), and encourages realistic expectations.

Figure 1:

Don’t Steal Their Dreams, but Temper Passion with Reason!

Realistic: Are there real career opportunities?

Effort: Effort and perseverance are appropriate mindsets.*

Adolescents: Adolescents need to become resilient.

Learning: Learning to be strategic is important.

*(Dweck, 2006)

For those students or children who are already entirely engaged in their passions which will lead to careers that are too competitive and likely go beyond their talents, Figure 2 provides reasonable strategies for dealing effectively with their passions without destroying all hope for their career directions. Only a very small percentage will be successful (Rimm, Rimm-Kauffman & Rimm, 2014) and should be encouraged to follow their talent.

Parents may invest thousands of dollars in specialized teachers, lessons and opportunities for their children if they overestimate their talents and wish them to only follow their passions. Being realistic and understanding children's limitations can save them frustration and heartbreak down the road.

Figure 2:

Strategies for Students with Passions in Highly Competitive Careers

Practice: Practice, practice passion area, so you determine the extent of your talent.

Alternative: Develop alternative skills in case passion opportunity doesn’t work out.

Strive: Strive to win in competitions, and join collaborations to compare your talent.

Skills: Select coaches to teach you high-level skills.

Install: Install a deadline for rethinking alternative career directions.

Opportunities: If opportunities are not realistic, select other direction.

Never: Never stop enjoying your passion, but make it into your hobby.

Students Who Are Not Engaged In Anything

Children who wander from activity to activity or who give up as soon as they meet a challenge can be lured toward engagement by much less extreme words than “passion.” Parents often try to encourage them to join an activity by saying such statements as, "You'll probably be really good at basketball if you just try." Although parents don't intend these words to cause pressure, anxious children typically interpret them as impossibly high expectations. Encouraging them to join in activities to develop friendships can assist them in getting started. Teaching children that a strong work ethic will help them to find their strengths and assuring them that there is time to explore their interests and capabilities will give them courage. Finding work experiences or mentors who inspire children can help them discover their interests. Figure 3 with its emphasis on interests, rather than passions, encourages children to become engaged in learning and to persevere.

Figure 3:

Strategies for Students with No Specific Interests

Interests: Interests can guide you.

Negotiate: Negotiate time to examine interests thoroughly.

Test: Test new activities with friends.

Explore: Explore multiple extra-curricular activities.

Raise Grades: Raise grades by working hard on school subjects.

Experiment: Experiment with part-time and volunteer jobs.

Search: Search for mentors and observe their work.

Tutor: Tutor young students to build confidence.

Serendipity: Serendipitous events or meetings can lead to opportunities.

Too High Expectations Lead To Underachievement

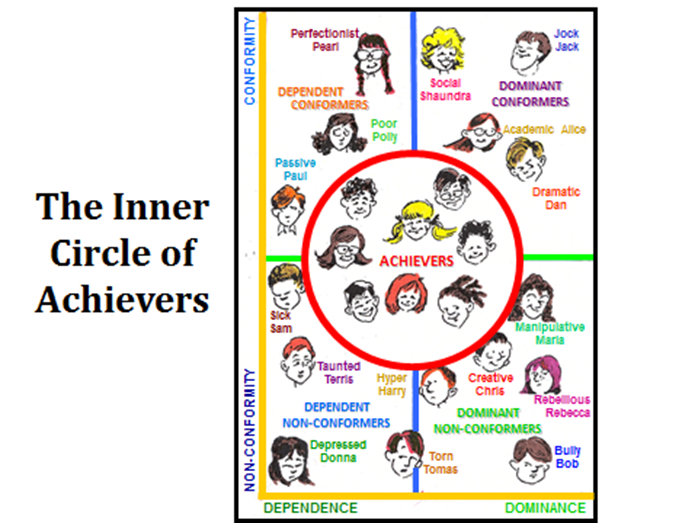

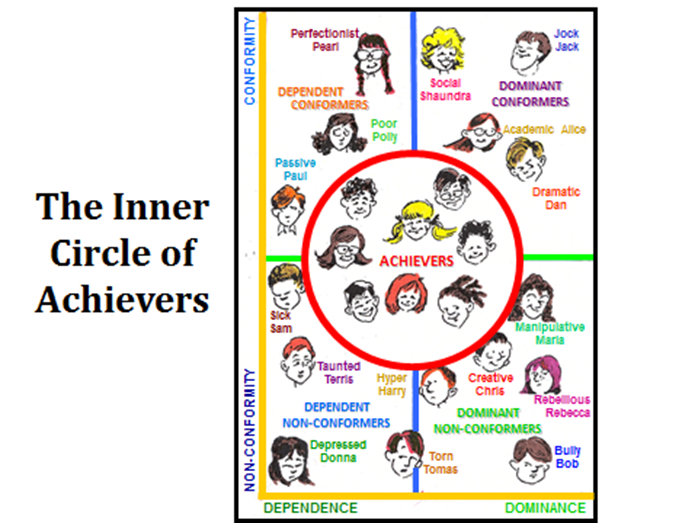

Figure 4 describes the paths that many gifted and creative children take when they feel extreme pressure to accomplish what they fear they are unable to achieve. I have excerpted here pages from my book "How to Parent So Children Will Learn" (Rimm, 2008, p. 14-17) that describes this figure:

Figure 4:

The children in the inner circle (figure 4) are achievers. They've internalized a sense of the relationship between effort and outcome - that is, they persevere because they recognize that their efforts make a difference. They know how to cope with competition. They love to win, but when they lose or experience a failure, they don't give up. Instead, they try again. They don't view themselves as failures but only see some experiences as unsuccessful and learn from them. No children (or adults) remain in the inner circle at all times; however, the inner circle represents the predominant behavior of achieving people.

Outside the circle are prototypical children who represent characteristics of underachievement. These children have learned avoidance and defensive behaviors to protect their fragile self-concepts because they fear taking the risk of making the efforts that might lead to less-than-perfect performance.

The children on the left side of the figure are those who have learned to manipulate adults in dependent ways. Their words and body language say, "Take care of me," "Protect me," "This is too hard," "Feel sorry for me," "I need help." Adults in these children's lives listen to their children too literally and unintentionally provide more protection and help than children need. As a result, these children get so much help from others that they lose self-confidence. They do less, and parents and teachers expect less. They become expert at avoiding what they fear.

On the right side of the figure are the dominant children. These children only select activities in which they feel confident they'll be winners. They tend to believe that they know best about almost everything. They manipulate by trapping parents and teachers into arguments. The adults attempt to be fair and rational, while the dominant children attempt to win because they're convinced they're right. If the children lose, they consider the adults to be mean, unfair, or the enemy. Once the adults are established as unfair enemies, the children use that enmity as an excuse for not doing their work or taking on their responsibilities. Furthermore, they often manage to get someone on their side in an alliance against that adult.

Gradually, these children increase their list of adult enemies. They lose confidence in themselves because their confidence is based precariously on their successful manipulation of parents and teachers. When adults tire of being manipulated and respond negatively, dominant children complain that adults don't understand or like them, and a negative atmosphere becomes pervasive.

The difference between the upper and lower quadrants in Figure 4 is the degree and visibility of these children's problems. Children in the upper quadrants have minor problems which they often outgrow. Parents who understand the potential for their worsening can often prevent them from escalating. If upper-quadrant children continue in their patterns, however, they will likely move into the lower quadrants. Most of the dependent children will, by adolescence, change to dominant or mixed dependent-dominant patterns. There are also some children who combine both dependent and dominant characteristics from the start.

Dependent and dominant children practice these control patterns for several years before they enter school. It feels to them that these behaviors work well, and they know of no others. They carry them into the classroom and expect to relate to teachers and peers in the same way that they have to their family. Teachers may be effective in improving some of the children's ways of relating; however, the more extreme the dependency or dominance, the more difficult it is to modify. Furthermore, teachers may respond intuitively to these children in ways that only exacerbate the problem. The dependency pattern often disguises itself as shyness, insecurity, immaturity, inattentiveness, or even a learning disability. Teachers may also protect these children too much.

The dominant pattern does not always show itself in the early elementary grades because the child feels fulfilled by the excitement and power of school achievement. Dominance may also be exhibited as giftedness or creativity, or, not so positively, as ADHD or a discipline problem. If it shows itself as a discipline problem, teachers may label these children negatively. The children may end up sitting next to the teacher's desk or against the wall with a reputation as being the "bad" kid of the class. Parents often refer to a dominant child as strong willed or stubborn.

Even if some teachers manage these children well in school, the dependent or dominant patterns may continue to be reinforced at home or in other classrooms. As time goes on, dependent and dominant children are likely to become underachievers because their self-confidence is built on manipulating others instead of on their own accomplishments.

In granting children appropriate power, we must give them sufficient freedom and power to provide them with the courage for intellectual risk-taking. However, we should also teach sufficient humility so that they recognize that their views of the world are not the only correct ones. Although we need to empower them enough to study, learn, question, persevere, challenge, and discuss, we cannot grant them so much power that they infringe on adult authority for guiding them. That authority is indeed more fragile for this generation's children than it has ever been.

For children with long-standing patterns of underachievement, adults make better progress by responding counter-intuitively. If children's goals are to be "most creative," "brilliant" and "best" or to "find their passion" and if they believe that reasonable goals will not be satisfying for themselves or for those who will love them, they will either listen to compromise and reset their goals to be more moderate with maturity, or they will continue into life as frustrated adult underachievers (Rimm, 1994). Here are 3 case studies:

*Case study #1:

Andrew had an early history of underachievement probably related to being both gifted and learning disabled. Math had never been his strength, but he was an excellent thinker and a very verbal young man. In high school he had reversed his underachievement, earned excellent grades, was a star in creative drama and had taken the initiative to build a "spook house" business that had been extraordinarily successful. He had netted a $10,000 profit from his enterprise. His motivation, hard work, imagination and creativity were remarkable and earned him an excellent scholarship for college. His successful entrepreneurship motivated him to follow his passion to major in business.

Andrew earned A's and B's his first year in college for his introductory business courses, but his second year included multiple math courses which caused him severe problems. TV screens, video games and socializing distracted him from his main agenda and the pressures of a broken romance and poor grades lead him to panic attacks and suicidal ideation.

Counseling and perseverance helped Andrew temporarily put his past girlfriend in perspective, decrease screen time and bring reasonably successful closure to his semester. A family session was intended to help Andrew set new realistic goals. Both parents were involved and they were discouraged and worried about their son. Andrew explained that he thought he should quit college and develop spook houses" as an enterprise because he believed he could make them into a successful lifelong business.

Both parents wanted Andrew to complete his college degree. Very reasonably, they were trying to guide him toward taking classes in his areas of strength, exploring new interests to manage his stress and to give him alternatives for his future. His very educated and intelligent father urged Andrew repeatedly to search for his "passions." Unfortunately, his loving father did not realize that his well-meant message to Andrew to find his passions was actually the message that Andrew was hoping to follow by dropping out of college. His extraordinarily successful one time entrepreneurial experience with the spook house was the emotional high he preferred to follow. A full college education would have given him more realistic choices for a good career for the rest of his life. Andrew was not passionate about studying and did not respond to his father at all. He believed that he had already discovered his passion and he saw no reason at all for a further search or study.

* This case study has been altered to protect privacy.

Case study #2 - Letter from an adult who is still searching for her passions

I discovered your literature while searching the Internet for insight into my life (as an adjunct to formal therapy), and what was written in your book, Why Bright Kids Get Poor Grades And What You Can Do About It(Rimm, 2008), resonated strongly with me. Parts of this book felt like a narration of my own life. Unfortunately, as a 30-year-old, the period of my life that aligns with that which you describe in your book is now over.

I have been told that I am "smart" and "bright" and I was enrolled in gifted programs in school, but I have always been plagued by chronic perfectionism, avoidance, and low self-esteem. Unfortunately, my achievement (or lack thereof) thus far in life reflects that. Are there resources available that detail any recourse for an adult who never reversed their underachievement problem?

Case Study #3 - Another letter concerning a search for passions

At the age of four I was labeled through testing as being gifted. I was then "branded" the genius of the family which often made me the center of attention. This caused me to place a huge amount of pressure on myself, and my mom also pressured me to be the first in my family to earn a college diploma. I was praised by adults for being smarter than others and kids who did not like hearing this shunned me. I even felt shunned by my siblings.

I have found it difficult to be "successful" in any profession and I feel a constant urge to move on when I reach a wall. I am a "Jack of all trades, but a master of none." First, I was a short order cook, and then I tried sales, and sold furniture, cars, and hi-fi equipment. I love customer service because I meet new people, learn their life stories, and they help me to remember that my life is not so bad.

On the other hand, my scientific side loves space, the stars, and learning about the physical universe. I also find myself to be passionate about the spiritual universe and the weird and wonderful ways it works. My greatest passion will always be music.

I continue to try to find out who I am. What I understand now, with your help, is that my aims are not too high. I have cruised through life just being mediocre in what I am faced with. I work hard, but not as hard as I could. I know that I can achieve success, but I put too much pressure on myself thinking that I have to be the best at whatever I set out to do. I just wanted you to know that those traits you spoke of do continue into adulthood. They can be strengthening, but can also be detrimental to motivation.

Graduation Message

I have heard many educators direct to students to find their passions. Many parents have also reminded me how much they want their children to be happy and find their passions. I have also heard multiple graduation addresses from middle school through university level that have urged graduating students to search for passions. In contrast, excerpts of my favorite and most meaningful graduation address was the following given by Dr. Steven Muller at Johns Hopkins University (Rimm, 2008, p.18):

As we congratulate you on your academic attainments and wish you well, it also seems more timely than ever to remind you…that you have received here a great blessing, and that therefore you bear as well a great responsibility. Whatever your field of study, you have been blessed by academic freedom in all fullness.

But let me also remind you that knowledge alone is not wisdom; that information is a means, not an end; that the object of free inquiry is truth, not profit; that freedom without responsibility is animal anarchy.

Finally, Figure 5 summarizes my Top Ten recommendations for bright young people to realistically and creatively steer their lives toward meaningful careers. They can guide young people toward developing strengths, engagement in their work, making real life contributions, appreciation for the education they have been given, achieving reasonable happiness and being able to support themselves and their families. It invokes both the freedom and responsibility advocated by Dr. Muller. I believe that educators who use my advice to guide young people will be more likely to lead them toward creative and fulfilling lives. As contributing adults who have set reasonable goals, they will likely hopefully also feel passionate about their work at least some of the time.

Figure 5:

My Top Ten Recommendations for Gifted Students to Fulfill Their Potential

1. Interests: Find a career that utilizes your strengths and interests.

2. Hard Work: Expect to work hard and persevere.

3. Competition: Good careers are highly competitive. You will win and lose, succeed and fail.

4. Independence: Don’t expect everyone to like and praise you. No one is perfect.

5. Humility: You will start at the bottom and are more likely to succeed if you help your supervisor to become successful.

6. Responsibility: Earn enough to support yourself and your family.

7. Tradeoffs: Life always involves some tradeoffs. You will need to make compromises.

8. Contribution: Make at least small contributions to our world. It needs your help!

9. Contribution: If you are highly successful financially, please give some back to those who made your success possible.

10. Reason: Following only passions is irrational. Uniting reason and emotion will allow you to enjoy your work some of the time.

References

Davis, G., Rimm, S. & Siegle, D. (2011). Education of the gifted and talented, (6th ed.) Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc.

Dweck, C.S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York: Random House.

Hostettler, S. (1989). Honors for underachievers: The class that never was. Chico, CA: Chico Unified School District

Marino, G., A life beyond ‘do what you love,’ (2014, May 17) New York Times

Rimm, S., Rimm-Kaufman, S., & Rimm, I. (2014). Jane Wins Again: Can Successful Women Have it All? A Fifteen Year Follow Up. Tucson, AZ: Great Potential Press.

Rimm, S. (2008). Why bright kids get poor grades and what you can do about it. Tucson, AZ: Great Potential Press.

Rimm, S. (1994). Why do bright children underachieve? The pressures they feel. How to Stop Underachievement, 4(3), p. 14-17, p. 18.

Rimm, S. (2008) How to parent so children will learn (3rd ed.) Scottsdale, AZ: Great Potential Press. |