GUIDING ANXIOUS CHILDREN TOWARD ACHIEVEMENT AND CONFIDENCE

Dabrowski’s Theory of Positive Disintegration (1967) has attracted much attention in the field of gifted education. His concepts of overexcitabilities and supersensitivities have helped many parents and educators to better understand and accept gifted children. Figure 1 includes an abbreviated list of intellectual, psychomotor, sensual, imaginational and emotional characteristics of gifted children researched by Dabrowski. The reader who reviews these characteristics easily recognizes that not all are positive and that some might cause children to have difficulties adjusting at home or in the classroom.

Dabrowski urged adults to accept the negative intensities as transitions in development and not to view them as symptoms of dysfunction or as disorders. There is, however, also great risk that some parents and educators of gifted children may misinterpret Dabrowski’s theory and assume that negative manifestations of overexcitabilities should be accepted in gifted children because they are part of defining these children as gifted. Concluding that children with compulsive talking, impulsive actions, cravings for pleasure or heightened anxiety should be allowed to work these problems out on their own or should be assured they are appropriate parts of their giftedness, can and does sometimes lead to serious problems and disorders. Although many gifted young people resolve their problems with time, too many do not. They may struggle socially or underachieve dramatically. It is an important goal of educators to develop children’s giftedness, but parents and educators require strategies for guiding children toward coping with, and in many cases, correcting problem behaviors. This paper will focus on practical strategies for redirecting intensity, impulsivity, oversensitivity and anxiety to productivity, fulfillment and confidence. Anxiety There is obviously a component of sensitivity and anxiety that is attributable to genetics. Some children are born with temperaments that cause them to be fearful or hesitant and less willing to take risks. As with all human characteristics, environment, experiences, and parenting all contribute to either worsening anxiety or overcoming much of it. Stress is not healthy for children or adults. Robert Sapolsky, in his book Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers (2004), pointed out how anxiety can lead to both mental and physical difficulties including depression, ulcers, colitis, heart disease and more. He also established that people feel less stress when they have made full effort and are reasonably optimistic about their reaching goals. They may recognize that there is a small chance of not being successful, but have a plan for dealing with that possibility and don’t consider failure to being catastrophic. Thus, if we are going to guide gifted children to helpful coping with stress, they must both internalize the relationship between effort and outcome and set reasonable goals. (Rimm, 2008) There are some components in the development of giftedness in children that can contribute to the pressures they internalize. The encouragement and enrichment that families provide is usually accompanied by significant love, attention and praise, from parents, grandparents, and often, even strangers on the street. The praise words that match the gifted child’s early and sometimes extremely precocious accomplishments can become too much of a good thing. Brilliant, extraordinary, smartest and other superlatives paired with actual high success in early schooling, can encourage gifted children to feel highly competitive and internalize extremely high expectations for themselves that is often referred to as “perfectionism”. (Rimm, 2007) When children internalize the relationship between effort and outcomes and learn to work hard to achieve their goals, we refer to that as motivation. Gifted children are more likely to be achievers if they learn to put forth effort and set reasonably high, but not unrealistically high, expectations for themselves. If their expectations are too high and they put forth good effort, they will be disappointed in themselves if they can’t achieve what they had hoped for. If they make little effort and their results are excellent anyway, they often assume that giftedness should be effortless. When challenge is presented, they may avoid it for fear that working hard infers they are not gifted. That avoidance of challenge causes them anxiety which worsens with continued avoidance. Gifted children who are fearful or sensitive and who have too high expectations and/or too little effort can become so anxious that they habitually either ask for more help than they actually need or attempt to avoid activities that cause them to be fearful. How they cope with their anxieties will either encourage them to become more courageous, reduce their anxieties and build their confidence, or increase their avoidance behaviors, make them more fearful and cause them to temporarily or permanently become underachievers.

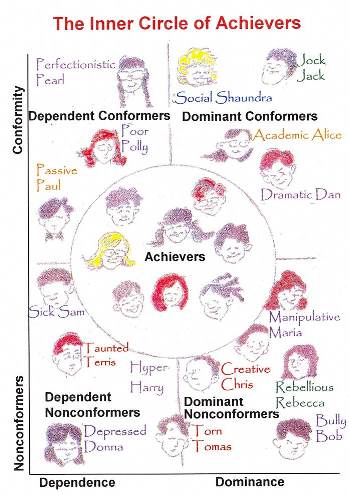

Source: Rimm, S.B. (2008). Why Bright Children Get Poor Grades and What You Can Do About It (3rd ed.). Scottsdale, AZ: Great Potential Press.

Students continue to be anxious and dependent as long as adults around them respond to them intuitively by doing too much for them, feeling anxious with them and granting them the inappropriate power to avoid or escape what they fear. The more these children avoid their fears, the more anxious they become and the more worried their parents feel. The children lose confidence in themselves, lower their expectations and their anxiety increases. The pattern can eventually lead to depression unless parent and child receive help, or the child is inspired by a teacher or other adult to gradually move forward to overcome fears and anxieties. Aristotle reminded us that "All adults involved with children either help or thwart children's growth and development whether we like it, intend it or not."

The following case examples of children and adults are actually combinations of several people so as to protect confidentiality. Case #1 – Dan Fears Speaking in Front of Class Dan, a gifted fifth grader, was extremely anxious and was on an Individual Educational Plan (IEP) for his disorder. Students were taking turns reading their reports to the class. His teacher made suggestions or comments to them about each of their talks. She also did that for Dan. He returned home after school and refused to go to school the next day tearfully explaining to his mother that the teacher had embarrassed him by criticizing him in front of the class. Dan’s mother was sad and anxious for Dan and angry at the teacher. His mother wanted to have Dan excused from speaking to the class as an IEP accommodation because of his anxiety disorder. If I had encouraged her to do that, Dan would have become even more fearful about speaking in class. Instead I recommended that the teacher make her suggestions privately for the first part of the school year, but that by the second semester, assure Dan that he was able to handle speaking and accepting suggestions openly just as other students do. Case #2 – Heather Fears Not Being Smart Enough Heather came to a school for gifted children in third grade after being in a heterogeneous class where she was not challenged. She had been far ahead of her classmates and known as one of the smartest kids in the school in her former school. After only a few days in her new school, she felt shy and anxious. She had stomachaches and headaches and said she missed her friends and the work was too hard. She tried to convince her parents to allow her to go back to her former school. Her teacher observed that although she was quiet in class, other girls were friendly to her and she was actually doing very well academically. I met with Heather to help her to adjust to not feeling “smartest”. I told her how pleased the teacher was with her work and explained to her the long term advantages of being in a gifted school. I asked the teacher to please be sure to give Heather a little extra positive feedback for her work or her thinking. I spoke to her mother about the importance of building her confidence in this challenging environment. Heather soon learned to love her new school and feel more confident. If her mother had returned her to her former school, she would have continued to be fearful in the face of challenge when she entered a larger middle or high school. Case #3 – Christopher’s Tears Empower Him Christopher’s parents were concerned about his unusual fear of new experiences. His mother explained that he was so fearful that he would not only cry frequently, but that she worried that he might actually have a panic attack. Christopher was the middle child in a 3-child family. His sisters were both high achievers. Christopher was a gifted underachiever and often cried at homework time, complaining tearfully that his work was too hard. The mother shared an example of how she had cancelled plans to take the children to the pool because Christopher tearfully screamed he was afraid to go. The father remarked to the mother referentially that Christopher had gone to the very same pool with him and had enjoyed it immensely and had not been at all fearful. Christopher overhead his parent’s conversation and became even more agitated. The family cancelled the fun excursion because of Christopher’s intensive, fearful reaction. I counseled the parents to offer Christopher two choices: they could arrange for a babysitter to stay with him or they could reward him with a sticker if he was brave enough to come and have fun with them. I explained that it was important to go ahead with their planned trip to the pool or Christopher would have been empowered by his tears to control the entire family. Commenting on Christopher’s courage instead of being overly sympathetic were also helpful in causing Christopher’s many fears to decrease in number and intensity very quickly. He also learned to do his homework independently when his mother changed her approach to feeling too sorry for him and doing too much for him. Case #4 – Margaret Opts Out (An Adult Case Study) Margaret, an executive vice president at an engineering firm was productive and successful for five years. The economy began struggling and the company ran into hard times and found it necessary to cut staff, most of whom were males. Staff were released with comfortable severance packages to provide them with support until they could find alternate employment. Margaret’s supervisor, who had always written excellent yearly evaluations about her made a reversal in her fifth year evaluation and was highly critical of Margaret, commenting specifically on her being too emotional. Margaret became both angry and anxious. She came to me for counseling during what she called an “anxiety crisis” complaining in tears about her boss turning against her. She shared with me that her boss’s critical evaluation had caused her so much anxiety that she wished he would lay her off with the severance package given to the men. Her boss who had labeled her as “too emotional” did not ask her to leave, but she felt ready to leave her high powered, well-paid position because of her anxiety. I encouraged Margaret to recognize that her formerly empathic, supportive boss was under pressure to cut staff and was probably hoping she would resign without a severance package—a very good, but not fair, way to cut costs. I encouraged her to respond in writing to the appropriate Board or CEO to cite earlier excellent evaluations and place on record what she believed was an unjust evaluation. I also encouraged her to continue to move forward to help her employer cut other costs. She should also search for other equal or better positions, but until she found one, opting out would permanently hurt her record, self-esteem and opportunities for other positions.

The first 3 cases were examples of parents who responded intuitively to children's fears and anxieties. They had learned that gifted children are sometimes very intense and oversensitive. Because they had read about the frequency of these characteristics in gifted children, they initially assumed that they needed to preserve these sensitivities, because they were part of their children’s giftedness. It was only after fears had become extreme that parents cautiously came to counseling for assistance in helping their children cope with their problems. They did not recognize that their “too supportive” approach to helping their children were in fact exacerbating the children's problems. These parents were very sensitive and caring, so they truly feared responding appropriately to their children because a firm, positive response would have felt harsh and inappropriate to them. They were anxious about the possibility of causing their children more stress. Instead they searched for ways to accommodate their children to save them from any struggles or worries, thus enabling them to avoid what they irrationally feared. In Case #4, the woman herself struggled with extreme anxiety, and instead of strategically planning how to overcome her difficult predicament, she searched for escape to avoid the horrific stress, but without thoughts of how she could serve herself better in the future. Again, her responses were intuitive, but not useful for her future. The strategy for teaching children or oneself to cope with anxiety is counterintuitive, but strategic and logical. If children are responding with anxiety (or an adult is), the counterintuitive response should use reason to overcome irrational emotions. Thus the adult in charge, whether parent, educator or counselor, needs to respond to anxiety with reassurance and firmness. The adult also needs to help the child set a path toward success and give the child tools for overcoming fears and moving forward. A six-step REASON plan for guiding children and a CHILL plan for children are included in Figures 3 & 4 and are also described in the following sections. Using REASON for Overcoming Anxiety! Here is the 6-step strategic plan for parents and teachers to use. Step 1: REALISTIC – Determine appropriate goal for the child (or adult). Begin with being REALISTIC about the goals you set for children and clarifying the expectations they have set for themselves. Gifted, anxious children typically set their own goals too high or too low or assume that parents have set them too high. Here are examples: - You could get an A if you tried. (Parent - too high) Parents can help children set realistic, moderate goals. The more realistic goals will immediately relieve children of some of the tension they feel. Children can also lower their personal too-high expectations and reduce their anxiety. It will be important that they not give up by lowering them too much. Step 2: EFFORT - Parents Will Also Want to Help Children Set Small EFFORT Steps. Steps toward speaking in class could be delivering the talk at home to the mirror first, then to parents and considering suggestions from mom and dad. A step toward adjusting to a new school might be setting a playdate with friends who share interests like music, art, science, or Legos®. Children can also learn to set steps for themselves. The boy in Case #3 could choose to come to watch at the pool and the woman in Case #4 could choose to come up with new money-saving ideas for her company. Step 3: ASSIST - Devise ASSISTive Tools or Techniques So The Child Can Move Forward. A child who feels afraid of the dark can use a flashlight (tool) to comfort him or play music (tool) to muffle imagined creaks. The boy who fears speaking could use a mirror (tool) to watch himself. The girl who is adjusting to class can have a friend stay overnight (tool) to assure her that a friend will be in her class. The woman’s tools can be a calm, written rebuttal of her criticism and a proposal for cost-cutting. The parents who work with the child on homework daily can help the child write a schedule (tool) for gradually doing homework independently. Step 4: SMILE - Positive Reinforcement That Encourages Without Pressure Helps Children Move Forward. Overpraise causes excitement that appears effective, but for underachievers it also causes anxiety and fears that they will disappoint adults and themselves next time. A pat on the back, a SMILE of encouragement that says “hang in there, you’re making progress” are the SMILE actions that keep anxious kids on track. For the child or adult, they only need to accept within themselves that they are moving forward instead of avoiding their challenges. Step 5: OVERHEAR - Children Who OVERHEAR Referential Talk of Their Progress Know That Parents and Teachers Are Noticing and Appreciating Their Efforts. Thoughtless, negative talk can impede progress. Deliberately planned positive discussion can be heard as supportive by children. Even adults who overhear conversations about positive changes can develop more confidence. Step 6: – NICE! - Small Rewards Selected By Children Can Be Motivating and Are Particularly Effective For Young Children. Stars and stickers are only effective temporarily, but fearful children need temporary support until they’ve moved past their fears to build confidence. Adults can also reward themselves with both praise words and activity rewards when they’ve overcome emotional withdrawals. CHILL to Cope With Anxiety Here is a 5-step plan to help children prevent anxiety. C – CHANGE Bad Habits into Good Ones If procrastination and play before work have caused you to avoid effort, set and follow a healthy schedule placing work before fun. H – HEAR Parents' and Teachers’ Words of Wisdom Your parents love you and both your parents and teachers want you to succeed. Adults have many years of experience and can give you wise advice. If you hear what they say and try their suggestions you’ll feel much better about your progress. I – INITIATE Small Steps of Effort Toward Reasonable Goals Be patient and realistic. Expand your work and concentration time gradually. Chart your progress so that you can visually see your improvement. L – LOWER or Raise Your Goals Appropriately You can dare to dream of great accomplishments someday, but for now set goals in small steps above what you have accomplished and consider that continued progress will mean success. When roadblocks deter you temporarily, don’t give up. Perseverance leads to accomplishment. L – LEARN What You Can Accomplish With Reason Instead of When you learn to break tasks down to manageable and reasonable chunks instead of feeling overwhelmed by imagining impossible-to-complete projects, your anxious feelings will diminish. You can concentrate on each small step and feel confident in accomplishment. The Quest for Self-Confidence Anxious children and adults typically describe themselves as lacking self-confidence. Those feelings lead them to avoiding challenges. They thus also lose the route to gradually building confidence. Children (or adults) cannot build confidence by only completing easy tasks because everyone knows that anyone can solve simple problems. It is only by tackling complex challenges, learning to break those into small parts, accomplishing them one step at a time and achieving goals, that children and adults permit themselves to gradually develop confidence and diminish the anxiety that has paralyzed and plagued them. We can redirect anxiety and oversensitivity to productivity and reasonable kindness. |

||||||||

©2008-2012 by Sylvia B. Rimm. All rights reserved.

Report any problems with this site to Webmaster@sylviarimm.com